The complexity and hype surrounding Large Language Models make it difficult to disentangle the arguments about generative AI’s potential harms.

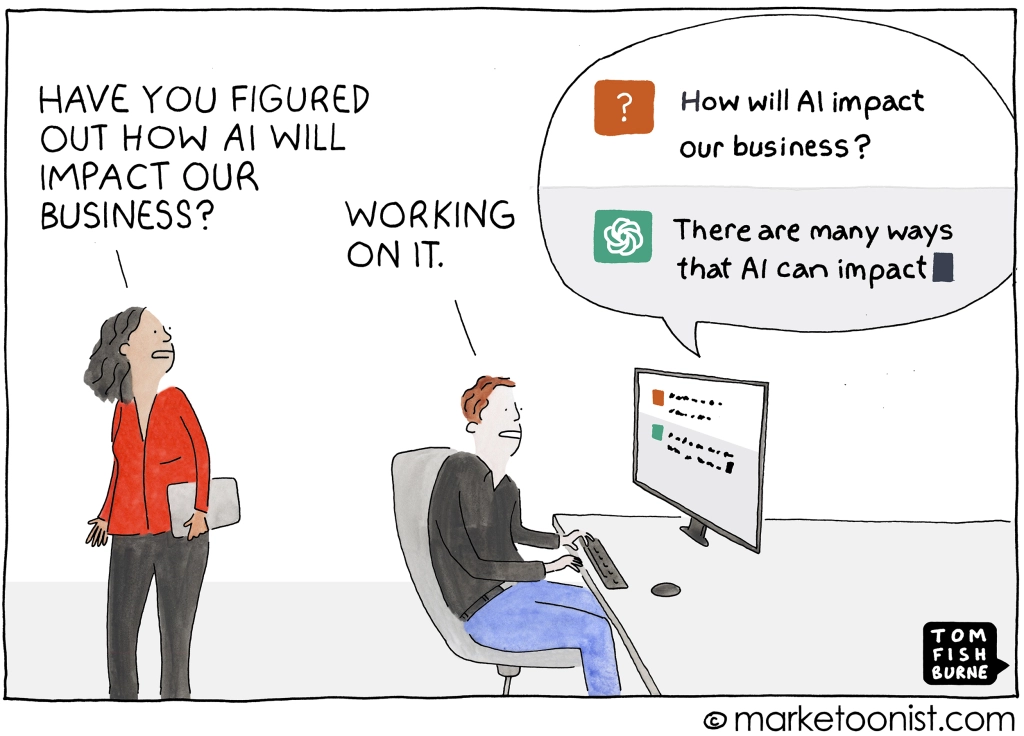

But one can have little sympathy for those who seek the assistance of ChatGPT to sort out their understanding of the issue.

It may be the strongest evidence yet of our species’ voluntary dumbification.

It may be the strongest evidence yet of our species’ voluntary dumbification.

On top of the hype there’s the spin from the industry itself. The recent confessional drama by big tech leaders warning of the risks and coming out in favour of regulation is alarming but doesn’t seem that genuine. Sudden talk of an existential threat betrays that they may have not been telling the whole story all this time and, worse, that they might actually have already lost control of AI’s “deep learning” process.

Yet, despite their collective concern, we know that independently they are doggedly trying to stay one step ahead of each other. And while this is certainly an opportunity for watchdogs to reach for thick red pencils we also know, rather depressingly, that regulators will always lag behind accelerating innovation.

Then there’s the language. Not the language of Large Language Models per se but that which is used by us when it comes to talking about them. We have been unable to defuse the linguistic traps that keep feeding the hyperbole. In an interview1 with the FT the science fiction author Ted Chiang protested about the use of personal pronouns when referring to chat-bots and lamented the anthropomorphic language such as ‘learn’, ‘understand’ and ‘know’ that are project on them to create an illusion of sentience where, he claims, none exists.

AI is not a conscious thinking intelligence says Chiang describing the term as “A poor choice of words in 1954”. Had a different phrase been chosen for it back in the 50s we would have avoided a lot of the confusion we’re having now. His preferred term for AI? “Applied Statistics”.

Consider the ‘writing professions’: Legal firms have already began to advertise the services of their AI driven “digital lawyers” who “accept” and “understand” legal questions and who not only connect a client’s questions to laws and cases but claim to draft bespoke documents for signature. Essentially, in Chiang’s applied statistics logic, these services are supercharged search engines that draw relevance on the basis of words (which they don’t ‘understand’) and then simulate existing text formats to produce prose in acceptable tone and syntax.

Aside from mismatched or entirely made-up results (there’s the recent case of the US lawyer fined for his chat-bot’s hallucinatory court citations)2 the engines lack comprehension of that which they deliver. Still, the client saves time and pays much less than the hourly rate a human lawyer would have charged for the work. There’s nervous excitement in the legal profession that entry-stage legal associates aren’t that necessary anymore. Of course, while legal AI is doing the work, entry stage legal associates are losing the capacity to learn to do it themselves, but that’s another story.

The same principle operates for data journalists who are assisted by AI that scrapes, sorts and catalogues swathes of data. Tools that sift through material identifying and matching information which journalists are then able to study for potentially dubious connections to expose wrongdoings. One hopes journalistic AI won’t soon be drafting the story. That should still require the journalist to challenge the veracity and value of the information, contemplate the repercussions, address the ethical dilemmas and employ the right language to make the story work. Not to mention avoid being SLAPPed3 by any clients of the legal AI community.

Yet with every passing month the capacity and popularity of Large Language Models is expanding. Despite their unreliability there’s a clear societal shift for the acceptance of their type of mimicry.

The result is that algorithmic systems take all the bad, incomplete -and let’s not forget often- malicious writing produced and feed it back into the large pool making it primary reference material that perpetually decays the information ecosystem. Shallow imitative writing that is hyped, even propagandist, is becoming an ingredient of our exchanges, a messy by-product of the cultural phenomenon we have embraced as ‘disruption’.

Throughout this year’s ChatGPT delirium from cheating on essays to writing marketing-speak and ‘supercharging’ businesses we may have forgotten that the skills developed by writing, questioning, double-checking and debating are what lead to better thinking and better judgment. At this rate the machines won’t really need to do much to achieve the much feared total take-over. We have already surrendered; willingly, unthinkingly.

Notes:

1. https://www.ft.com/content/c1f6d948-3dde-405f-924c-09cc0dcf8c84

3. SLAPPS: https://www.the-case.eu/

Cartoon by Tom Fishburn