The Late Career Switch

Lucy Kellaway had a dream job. Her self-proclaimed title was Chief Bullshit Correspondent for the Financial Times though in polite company she’d describe herself as an observer of the peculiarities of corporate culture. Her weekly columns deconstructed corporate press releases and deflated the bloated egos of management gurus. She interviewed hot shot bankers and massacred CEOs making flatulent statements. If she showed up at your AGM it was not to value your company’s share price; she was there to expose the “heinous guff”.

After graduating from Oxford with a degree in Philosophy, Politics & Economics – the academic equivalent of a train ticket for the front carriage of the British ruling class – she took a stab at banking at J.P. Morgan and, in 1985, walked through the old doors of Bracken House for a lifetime at the FT.

She resigned in 2017, 32 years and 1023 columns later. In her book Re-Educated: How I changed my job, my home, my husband & my hair released this summer by Ebury1 she explains why. More entertainingly she recounts how she reinvented herself and ended up teaching Maths and later Economics at inner city comprehensives in London’s poorest boroughs.

She resigned in 2017, 32 years and 1023 columns later. In her book Re-Educated: How I changed my job, my home, my husband & my hair released this summer by Ebury1 she explains why. More entertainingly she recounts how she reinvented herself and ended up teaching Maths and later Economics at inner city comprehensives in London’s poorest boroughs.

It was not so much the decision to leave her ‘swanky’ job that was ‘brave’ as her friends and colleagues discouragingly told her, but it was what she did in the transition that became the most instrumental aspect of her journey. Not only did she convince others roughly her age (she was 58 at the time) to join her but with her friend Katie Waldegrave they founded Now Teach2 a charity that entices professionals near the end of their careers to consider re-training as teachers. In the midst of a teacher recruitment crisis in the UK the Now Teach website says it has been “a colossal waste” that no one had never successfully managed to recruit experienced people into teaching.

Before resigning Kellaway consulted an online life-expectancy calculator and answered a series of questions ‘mostly honestly’ and was reliably informed that she is likely to live until she is 93. She was also encouraged by the new gerontological division of old age into two classes: Young-Old and Old-Old. The former identifies those between 60 and 75, the period “when you are healthy and can still do most things.”

It is rarely considered strange when executives or politicos leap into academia and take on professorships but it does seem odd to see someone step into a secondary school classroom. The latter is of course more complicated. It’s probably a status thing as well. Now Teach maintains that this older class of professionals not only brings wisdom, experience of the world, fresh ideas, perspective and careers advice but status too and “may offer solutions to some of the more intractable problems our schools face”.

Whether they have the stamina, the patience and the willingness to suffer the huge salary cut that comes with it is another matter. In their first year qualified teachers earn between £24,000 and £30,000.

Kellaway landed in a school “built on the broken windows theory of policing where pupils who get yelled at for putting their hands in their pockets are considered less likely to throw desks or stab each other”. She agrees that such children are more likely to do their homework, get decent results and have a better start in life. But she is torn when on her very first day she sees a nervous pupil vomit during assembly.

Re-Educated is a unique and meaningful story; it is cleverly structured and despite the brutal self-analysis it is elegantly told mostly because Kellaway tells it without bullshitting. But more significantly the book captures England’s social inequalities, the deteriorating state of the education system, the difficulties of parenting and of course the mystery of the savage but rewarding experience of being a teacher.

And because once-a-journalist-always-a-journalist the book’s greatest moments come when Kellaway the journalist observes Kellaway the teacher and deftly describes her own humiliations when she loses control of her class and the stress of talking to a parent about their child’s poor performance.

When Kellaway was a child she attended the Camden School for Girls where her mother taught English. When she meets people she knew at school most don’t remember her but they remember her mother. Her mother’s death, almost a decade before she took the plunge, was the first time quitting the FT crossed her mind. She made up her mind when her father died.

Kellaway’s own daughter, Rose, also became a teacher. Unlike the Now Teach troupe Rose went straight into teaching after university. It is not right to feel jealous of your children says Kellaway but recounts how along with pride she did feel envy when a particularly difficult boy gave Rose a Christmas card on which he’d written “You’re awesome, Miss”.

One evening, after they had become colleagues, Kellaway begins to recount a difficult conversation she had with the parent of one of her worst Year 11 students. Rose interrupts her: “Mum, let’s not talk about school stuff.” Rose, writes Kellaway, “had spent ten hours at the coal face in a much tougher school than mine. And now she wants some life. I, on the other hand, am still new enough to teaching and still so in thrall to the whole thing I don’t want any other life at all”.

Kellaway confesses that she decided to leave her job at the FT because she wasn’t getting better at what she did. Her writing, she claimed, was no better than what it used to be. In fact, sometimes she thought it had actually gotten worse. On the evidence of this book that is bullshit.

1. https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/1120365/re-educated/9781529108002.html

2. Now Teach: https://nowteach.org.uk/

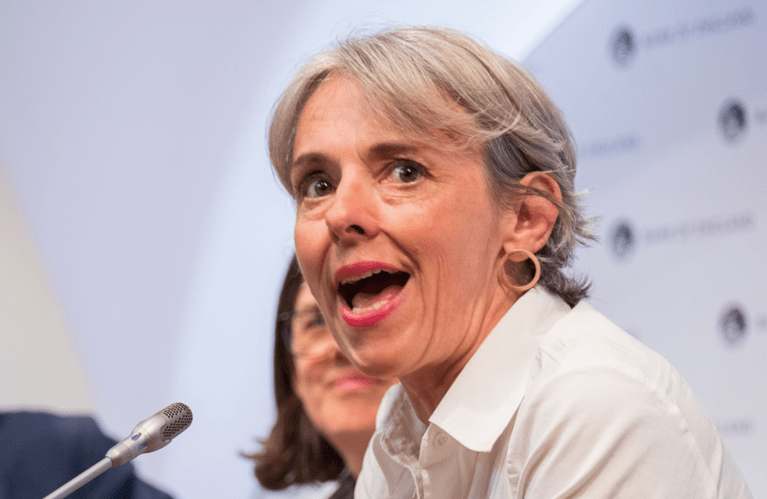

Photo from the Now Teach website