The structures of the Turkish Cypriot Community – From Minority to Community

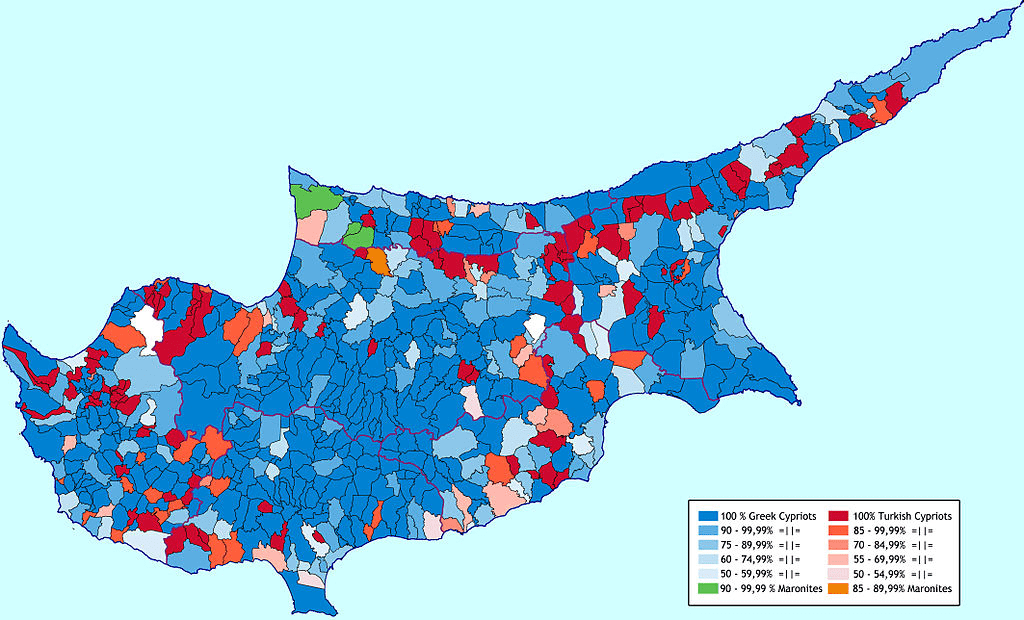

According to the 1881 census, the inhabitants of Cyprus were 186 thousands.

Of those, 137,631 were Greeks and 45,458 Turks, while the rest were of other ethnicities1.

As the historian G.S. Georghallides wrote, «the Turkish minority owed its very existence to the Ottoman conquest, for three centuries its political position being a facet of Ottoman rule».

As the historian G.S. Georghallides wrote, «the Turkish minority owed its very existence to the Ottoman conquest, for three centuries its political position being a facet of Ottoman rule».

He also states that this minority consisted of various components: soldiers who took part in the Turkish conquest of 1571, settlers from Anatolia, Latinos who converted to Islam after the conquest and “a large number of autochthonous Greek villagers who, during the worst periods of Ottoman tyranny, indigence or fiscal oppression, were forced to espouse Islam»2.

During the British colonial rule, the Turkish Cypriot minority has, in general, the same structures as those of the Greek majority. The ruling social class consisted of the large landowners(tsiflikades), whose urbanization was delayed in relation to the Greek landowners. To a certain degree, this delay can be attributed to cultural and religious reasons linked to the situation in Turkey. The urbanization of these social layers will be linked to the Kemalist reforms in Turkey. The mass of the Turkish Cypriot population is rural and faces the same problems as the corresponding Greek masses. However, the situation of the Turkish Cypriot peasants is to some degree better, given the fact that , as a legacy of the Ottoman period, they own more fertile land than that of the Greek peasants.

Within the Turkish Cypriot minority, a position similar to that of the Church, from a financial point of view, holds the religious Muslim Foundation EVKAF, with a huge property that at the time, has annual income around one million pounds3. EVKAF’s property was managed by a committee appointed by the colonial government.

The fact that, during the Ottoman occupation, the ruling Turkish Cypriot class consisted of administrative lords and landowners did not encourage economic initiative in commercial areas which was left in the hands of the rayas (ραγιάς, derogative reference, amounting to a servant, for non-muslim people in the Ottoman Empire). In a way, this tradition continued in the first years of English colonial rule. However, it would be wrong to assume that Turkish Cypriot landowners were not involved in commercial transactions. As in the case of the Greeks, a large group of them lived in the cities and managed commercial shops. They were also usurers and managed large urban property, shops and hotels, the well-known hania (χάνια, i.e. inns)4.

Testimonies that we have indicate that from a very early stage the British tried to keep under their absolute control the Turkish Cypriot community in order to use it as a leverage to the national claims of the Greeks of Cyprus. The well-known Turkish Cypriot politician, doctor Ihsan Ali, writes in his memoirs that it had become a tradition for the British to recognize two “chieftains” for the Turkish community, the head of EVKAF and the Mufti5.

AKEL, in its 1952 program, states that “under British occupation, minorities, and especially the Turkish minority, realize their education and their religious institutions enslaved to the English. The Mufti is appointed by the British Government and the colossal fortune of EVKAF which generates over one million pounds a year, is managed by a committee appointed by the government”6. It should be noted here that AKEL tried to organize the Turkish Cypriot workers in its ranks. The participation of Turkish Cypriot workers in AKEL’s trade union organization, PEO, was of considerable importance. Even in 1958 “PEO had three and a half thousand Turkish Cypriot members, and the Turkish Cypriots were represented in the provincial committees of PEO in Nicosia, Limassol and Famagusta. Turkish was the second official language at PEO meetings “7.

Turkish Cypriots participated even in the right-wing Pancyprian Farmers Union PEK, in the first years of its life; later they left, due to the pressure of nationalist Turkish circles, to establish the Union of Turkish Farmers. In fact, Andreas Azinas, one of the leaders of PEK, repeatedly stated in his public statements that out of the 7 members of its Supreme Council, two were Turkish Cypriots.

The Turkish presence remained important in the colonial bureaucracy and especially in the police. In the beginning of the 20th century, the police force of Cyprus consisted of 281 Turks and 387 Greeks8. This was not only due to the British encouragement but, as the Turkish Cypriot scholar Ibrahim Aziz pointed out, also to the fact that the Turkish Cypriot landowners, cut off from the trunk of the same class in Turkey, “engulfed the British administration to prevent the Enosis (Union with Greece)”9.

Another Turkish Cypriot scholar, Niyazi Kizilyurek, wrote that “the Muslim ruling class of Cyprus allied with the colonial administration due to its own interests. Thus, it secured its own position, while at the same time ensuring the continuation of colonialism “10.

There are, in any case, complaints by the Greek side about favorable treatment of the Turkish Cypriots in the recruitment to the public service and in the provision of scholarships for further training in England, a precondition for their promotion to senior and top civil servants.

This Turkish Cypriot ruling group of the period up to the 1920s is tied to Ottoman traditions and Islam and opposes the Kemalist Turkish nationalism that is developing in Turkey. That is why it will be confronted by a new group of nationalist politicians backed by Turkey. However, as it was pointed out “the absence of a Turkish Cypriot bourgeoisie with national goals, capable of fighting against British colonialism, made it impossible for the nationalist awakening of the 1920s to transcend the limits of an elitist movement. This, in turn, meant dependence on the pragmatist policy of the Turkish ruling class.”11

Besides, this nationalist group, which until the 1930s aspired to anti-British sentiments, was transformed along and to a degree the Turkish-British relations were being improved. Niazi Kizilyurek mentions that Turkish Foreign Minister Dr. Aras (Tevfik Rüştü Aras) assured the British ambassador in Ankara, after complaining about the role of some Kemalists in Cyprus, that “every Kemalist is a friend of Britain. This is the acceptable policy by the Turkish government and Ataturk’s personal wish. If any people among the Turkish Cypriots try to create an atmosphere of enmity between Turkey and the Cypriot government, they should be exposed as enemies of the Kemalist democracy”.12

It is in this climate and these new conditions that the Turkish Cypriot ruling class “accepted that its own interests be determined by Anglo-Turkish relations, because these were not the strong and clear interests of a class, but the narrow interests of a bureaucracy.”13.

After all, according to some analyses, the fact that “the Turkish Cypriot ruling group consisted largely of members of the Administration, who were directly dependent on the colonial government and landowners made feasible the control of the Turkish Cypriot community institutions by the British colonial government”14. Thus, the Turkish Cypriot education remained under British control until independence and the EVKAF, the Muslim religious institution, until 1948.

The absence of political structures in the Turkish Cypriot community was due, as emphasized, to the absence of the idea of a “national” community, since the concept of the nation-state did not exist within the framework of the Ottoman Empire15.

But in the 1940s, things in the Turkish Cypriot community changed rapidly. In 1943 the Katak organization from the initials Kibris Adasi Turk Azinligi Kurumu (Organization of the Turkish Minority of the Island of Cyprus) appeared. This organization is led by those urban section which are inspired by the principles of Kemalism. Katak was the first mass (or grass roots) Turkish Cypriot political organization and according to information provided by Turkish Cypriot researchers as well, it was founded at an English instigation in order to oppose the Greek Cypriot demand for Union with Greece16. Among the founders of this organization was Dr. Fazil Kucuk who later founded the National Party and was vice president of the Republic of Cyprus at its establishment. An important remark that could be made about this organization is the fact that the Turkish Cypriots themselves at that time, considered themselves a minority. It is even reported that intense discussions took place among the 76 founding members of the organization as to whether the word minority or the word community should be used. In the end, the idea of using the word minority prevailed17. Since then, however, Katak pushed for the establishment of separate Turkish Cypriot organizations and has strongly opposed the existence of inter-communal organizations. Thus, for example, in 1944 there was withdrawal of Turkish Cypriots from PEO and Turkish Cypriot unions were established.

The first political parties in the Turkish Cypriot community were founded a little later, in 1945. They were the People’s Party of Fazil Kucuk, later renamed to Turkish Cypriot National Party, and the Independence Party founded by Necati Ozkan. The evolution of successive renaming is characteristic of the development of nationalist ideology within the Turkish Cypriot community. Thus, in 1955, Fazil Küçük’s party was renamed to “Cyprus is Turkish”18. An important milestone in the political organization of the Turkish Cypriots was the establishment of the Federation of Turkish Cypriot Organizations in 1949. Political parties, such as that of Fazil Küçük, also participate in the Federation. After all, Küçük has been playing a leading political role in the Turkish Cypriot community since the late 1940s.

Rauf Denktash also appears in the same time period. In 1948 he ran with Fazil Küçük’s party for municipal elections, but shortly before the elections withdrew his candidacy and accepted an offer from the colonial government to work in the Public Prosecutor’s Office and later, in 1953, as Assistant Attorney General. A few years later he resigns from this important position and takes over the presidency of the Federation of Turkish Cypriot Organizations. He thus becomes the second important political figure in the Turkish Cypriot community, after Fazil Küçük.

From what was mentioned above, it is clear that the structures of the Turkish Cypriot minority are gradually changing after the Second World War. The formerly self-identifying Muslim minority is now transforming into a Turkish Cypriot. However, its structures remain controlled as in the previous period. The difference is that as a Muslim minority it was controlled mainly by the British. As a Turkish Cypriot minority, control is gradually transferred to Ankara; however, co-operation with the colonial government, which continued until independence, has not ceased. A Turkish Cypriot journalist characteristically noted the following: “Turkey is a reality in Cyprus, and it has various demands: he who gets into politics, if he is not act aware of this fact, he will not have the opportunity to put on his clothes again.” Further, he notes that the leadership of the Turkish Cypriot community is taken over by the one who holds the “seal” of Ankara in his hands.19 This has been verified to this day, when Ankara, for its own interests, ousted two historical leaders of the Turkish Cypriots, Fazil Kucuk and Rauf Denktash.

Another new element in the structures of the Turkish Cypriot minority in the 1950s is its relative urbanization. The new urban layers consist of traders as well as independent professionals. Young scientists, lawyers, doctors, teachers and others take on the political leadership of the minority. Next to these bourgeoisie there is always a strong civil service group, integrated into the colonial administrative mechanism. These new social strata are interconnected with Kemalist ideas. Many of the young scientists are now studying at Turkish universities, although the civil service elite goes through the English schools of Cyprus and then a part of it through the English universities.

With the disproportionate rights and the recognition given to it as a community with the Zurich-London agreements of 1959, the issue of the Turkish minority has taken on a new dimension. In connection with these rights, the question arises whether the Turks of Cyprus are just a minority or, as Turkish historians and other social scientists upgrade it after the invasion of 1974, they are a “second people”. The term “second people” is not legally or politically acceptable, especially in the case of such a small geographical area. If for Cyprus the notion that the Turkish Cypriots are a “second people” was accepted, then why not accept the same notion for Afroamericans in the US? Moreover, by the same logic, hundreds, if not thousands of minorities around the world, could claim not the rights of a minority, but those of a people that can lead even to the right of self-determination. This would, of course, mean the multisplitting of the planet in many thousands of little states. Even the terminology used today for two “communities”, essentially upgrades the Turkish Cypriots to the detriment of the Greek Cypriots. Until the 1950s, if one looked at the Turkish Cypriot sources themselves, one would find that the Turkish Cypriots themselves identified themselves as a minority. The same goes for the definition given by the colonial administration and London in general. In any case, the granting of rights to the minority, the possibility of its political partnership with the majority as a measure of its collective protection, should not result in the neutralization of the political will of the majority as was done with the Zurich-London agreements and even worse, with the Annan plan. As it has been mentioned “the Republic of Cyprus was unfortunately built on the basis of the neutralization of the rights of the majority of the population by its minority” and this was one of the main causes of the crisis that followed.20 It is for this reason why, for a lasting solution to the Cyprus problem, the mistakes of the past should not be repeated. Which means that the individual and collective rights of the Turkish Cypriots should certainly be protected, but not to the detriment of the majority, in this case the Greek Cypriots, nor in a way that violates the basic rules on which all democratic societies function. Nor is it possible to abolish the national identity of Turkish and Greek Cypriots in order to create a new Cypriot greenhouse identity, as suggested by some neoliberal and postmodern historians and social scientists. Where applied elsewhere, experiments of this kind, failed. On the contrary, their national identities can coexist in a common political identity(citizenship) within the Republic of Cyprus. National identity emerges through historical, socio-political and socio-economic processes of centuries. It is not produced in any political greenhouse and for sure cannot be imposed.

The Turkish Cypriots after 1974

Developments after 1974 led to the full control of the Turkish Cypriots by Turkey through the occupying army. Of course, this control existed before 1974 as well but was territorially limited to the Turkish enclaves, which were scattered throughout Cyprus. Furthermore, they circulated without problems outside these enclaves. After 1974 and their obligatory transfer to the occupied zone, a new situation was created. Any contact with the Greek Cypriots stopped. Ankara first promoted the creation of an entirely Turkish Cypriot administration and then in 1983 pushed for the creation of the so-called “Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus”. This secessionist action was condemned by the United Nations Security Council and no country other than Turkey recognized the occupation regime.

The negotiations, which from time to time took place under the auspices of the United Nations, did not yield results, since Ankara’s goal was not the partition any more but, instead, the strategic control of the whole island. When in the last round of these negotiations between Rauf Denktash and Glavkos Clerides things led to the Annan plan, Turkey was very close to achieving its goals. Thanks to the support of Britain and the United States, it has been able incorporate into a United Nations plan, all of its claims, which were satisfactory to its long-term strategic goals. Rauf Denktash, who was an ostensible obstacle to the acceptance of the Annan plan, insisting on extreme positions which – at that time- did not serve the Turkish strategy, was removed from the leadership of the Turkish Cypriots.

Although this removal in a well set up scenario, it was presented as the result of an “orange” revolution which was applauded by the British, Americans and the European Union. Something that the leftist Turkish Cypriot journalist Sener Levent deconstructed as an argument. Responding to Greek Cypriots who spoke of a “betrayed uprising” of Turkish Cypriots by the No of their Greek compatriots, he wrote:

Uprising is not a usual word. It contains deep meanings. Against what is a community rising up? Of the system. Of the regime. Of the dictatorship. Of the conquerors. Of the colonialists. Well, what is our situation after 1974? Are we not under occupation? Has not our political will been violated? If there is going to be an uprising, shouldn’t it be done first of all against our conqueror? Well, in the days of the referendum, did you see such an uprising here? Or do you think that there is always an uprising whenever thousands of people gather in the squares? These squares have been filled and emptied many times in our history. Remember. Remember how that square was suffocatingly filled on November 15, 1983 when the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus was proclaimed. Or when Bulent Ecevit set foot on the island after July 20th. It was a ramp, wasn’t it? Why was the rally organized by the Turkish Cypriots to say “yes” to the Annan Plan an “uprising”? These rallies were not organized against Ankara, but together with Ankara. Sponsored by the United States, Britain and the EU. Applauded by US Ambassador Michael Klosson, US Special Representative Thomas Weston and British Lord David Haney. Weston was uncovered by honoring our rallies with his presence. Do you call this an uprising? Do you consider these demonstrations that took place under the security of the wings of the conqueror of the island as an uprising? How can an uprising break out in a country and no one’s nose bleeds? Have you ever seen anything like this in history? Wasn’t the whole issue the forcing of a “yes” and a “no” from that referendum? ……………………………………………………………..……….……………This was hardly an uprising. It was obviously just a deception of a community. It was not the Greek Cypriots who betrayed it, but those who dragged her to the squares for their own interests. After all, this betrayal was soon understood. The country was looted once again. The conqueror received its “certificate of innocence”. While those who rose up took hot air21.

The Turkish Cypriot demonstrations in support of the Annan plan, in 2002-2003, which led to Denktash’s ousted, were essentially organized under the guidance of Ankara and the Americans. The latter indirectly even financed the whole operation, while at the same time, they took care of presenting these events as a spontaneous popular uprising. Characteristically, a whole series of articles by Sener Levent reveal how the whole scene was set up. Levent repeatedly referred to this issue and spoke of a setting with reference to Soros and the Americans, as well as to the infamous “orange revolutions” organized elsewhere. For example, responding to the Greek Cypriot journalist Alecos Constantinides who spoke about a “revolution” of the Turkish Cypriots in which they overthrew Denktash and replaced him with Talat, he wrote:

I started this topic yesterday and I continue today. Did you say that “the Turkish Cypriots made their own revolution” dear Aleco? I wish we had done it. Did you confuse us with other revolutionaries? Was it with the Algerians who drove out the French colonialists? With the Cretans who drove out the Ottomans? Or maybe with the Czechs or the Hungarians? You know. They were lying under Russian tanks in Prague and Budapest. They threw stones at the soldiers in the tanks with slingshots for the birds. What are we Turkish Cypriots doing here? We throw flowers. We greet with admiration the military planes that do stunts every 20th of July. Our leader passes in front of the military commanders showing his gratitude. Our former leader, who is now 84 years old, watches them with pleasure sitting in an honorable position in the protocol. He photographs them with his digital camera. He immortalizes these proud historical moments. This leader of ours is the one you call “deposed” Alecos. This happened neither to Ben Bella in Algeria, nor to Sukarno in Indonesia, not either to the Shah of Iran, or the junta generals in Greece. They were all deposed when they were overthrown and could not sit in the honorary gallery again; no one could, except our “deposed” leader. Is this what you call “revolution”? Look at what happened here after what you call “revolution”. Because I’m sure you do not know. If you knew, would you have called it a “revolution”? After those massive rallies with our conqueror that the late Thomas Weston applauded we were absorbed in the magic of the “orange revolution”. We rejected Marx and loved Soros. And after realizing that looting and spoliation are very much in the spirit of the revolution, we fell like hungry wolves on your last properties that were left here. We brought just as many people from Anatolia here by ferry. We reinstated them. Your fortunes are gone. Even those who came here wearing only their underpants gained millions of pounds! Naturally, you blame the Greek Cypriots because they always say “no” to this case. And you keep writing that “had you said ‘yes’ to the plan these things would not have happened? Who said it, that it would not happen? Who said that Turkey would have implemented that plan had you said “yes”? How many times have they admitted to saying “yes” because you would say “no”? Mercy dear Alecos, nisafi. So you still do not understand: that plan was a trap set for all Cypriots? In the end is it possible that this was not a referendum? Was it written anywhere in this account that those who said “no” would be punished? Is there respect for those who said “yes” while there is no respect for those who said “no”? What kind of voting is this? You said revolution, huh? Look now how everyone here became supporters of partition. This is where the half a century dream of the leader, that you consider as overthrown, came true. If in the past there were some here who raised their voices in these squares against our conquerors, they too have disappeared now. They all became slaves of Ankara. Is this what you call a “revolution”? ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………(Our new leader, Mehmet Ali Talat) had a makeup. He shaved his head. He changed his glasses. And our “revolutionary” leader came to us after taking “image” lessons from experts in Ankara. He speaks. Takes struggle lessons from the deposed leader. And he returns with new instructions from Ankara, where he goes often. And he appointed an eloquent representative. Every day he attacks the Greek Cypriot side. Turkish Cypriots send out an emergency signal, S.O.S. What kind of revolution is this, Alecos?22

Certainly, the Turkish plans were favored by the conjunctures of the time. In Ankara, the Islamic Justice and Development Party (AKP) won the elections in November 2002 and formed a government under the supervision of the Kemalist military-bureaucratic establishment. As Turkey’s European course imposed some political stability in Ankara, political Islam and the Kemalist bureaucracy were attuned in the context of a historic compromise that had long since begun. Within this context of compromise, the neo-Ottoman model of foreign policy, which also had its roots in the past, was firmly adopted. On this basis the Annan plan was accepted after all the essential Turkish demands were met. Thus, the generals gave the green light for the change of guard in the occupied areas from Raouf Denktash to Mehmet Ali Talat.

The whole operation of the Annan plan aimed at the de-incriminating of Turkey, which appeared to support a solution plan that had the seal of the United Nations. This is emphasized once again by the Turkish Cypriot leftist journalist Sener Levent, who has been repeatedly persecuted by Denktash’s occupation regime. Specifically, he wrote:

I do not consider our rallies for the referendum an uprising. There cannot be an uprising under the protection of the occupying forces of the island. Above all, there cannot be an uprising our rallies which were applauded by the representatives of America and England. I have written my views on the Annan Plan many times up to today. I believe that this plan was prepared for Turkey, not for the Cypriots. To relieve Turkey of the problems related to Cyprus in the process of its EU accession and to pave the way for it. After all, this was proven during the time that has passed since then. The road was opened for Turkey. Thanks to our very precious “yes”. And thus our road was completely closed. The Annan Plan was a trap set for the Cypriots23.

As part of this communication policy, Ankara also opened the roadblocks that had kept the Turkish Cypriots isolated until then. But even this opening also took place under the Turkish conditions of the indirect recognition of independent Turkish Cypriot authorities. In addition, the opening of the roadblocks breathed new life into the economy of the occupied areas and eased the financial burden of Ankara, which maintained them. Whereas, some extremist nationalist circles in Ankara opposed the Annan plan, since all the demands of the bureaucratic- military establishment were met, it was natural to give the green light for the Turkish Cypriots to approve it in the referendum that followed. After all, even if the Turkish Cypriots were against it, Ankara, using the settlers who were also allowed to vote, could easily impose its policy.

Besides, the most important part of the Turkish Cypriot bourgeoisie also had an additional reason to unreservedly support the Annan plan. For the first time, the accession of Cyprus to the European Union opened new economic horizons. This was also the case for the ordinary Turkish Cypriots, to whom the European Union was presented as a paradise that would solve all their problems. From one point of view, this communication policy regarding the European Union was not without value for the Turkish Cypriots. They were living under difficult economic conditions, their human rights were not being respected and therefore the Annan plan opened new horizons for them. Naturally, there were those, a small minority of course, who foresaw the Anglo-American plans and had the fear of future turmoil that an unjust solution would cause. In general, however, all the conditions were in favor of the approval of the Annan plan. After all, promises were generously given by both the Anglo-Americans and the European Union. The foreign factor gave more weight on satisfying all kinds of Turkish demands because it considered the Greek side for granted. Judging by the fanatical support given to this plan by the Simitis government in Athens and that of Glafkos Clerides in Nicosia, as well as by the fact that European Union, Americans and English officials spoke about deception by the Greek side, rumors are rather confirmed that Athens and Nicosia had made commitments to the foreign factor. Even when they lost power, George Papandreou as the new leader of PASOK and Glafkos Clerides with Nikos Anastasiadis as head of the official DISY, they fought to the end in favor of the Annan plan. This, after all, explains the post-referendum reaction without limits by the foreign factor against the Greek Cypriot side because it dared to oppose this plan. But of course, referenda aim at enabling the people to decide on something that is proposed and not to legitimize something that others have decided on their behalf. In the case of Cyprus, Cypriots were condemned and proclaimed guilty because of the way in which they exercised a democratic right. The anger against them was so much that some claimed that the adoption of the principle of the referendum was wrong and that the approval of the solution based on the Annan plan could have passed much easier through the Cypriot Parliament. The British mediator David Haney, angrily stated that the plan would be reinstated as many times as needed until it was accepted by the Greek Cypriots24.

The negotiations that followed after the rejection of the Annan plan dealt with the internal constitutional issue. Only in the last rounds of these talks, at the insistence of Greek Foreign Minister Nikos Kotzias, was the international aspect of the problem raised. The issue of the cancellation of guarantees and the withdrawal of the Turkish occupation troops was raised. Something that was rejected by Turkey in the last round of talks in Crans Montana.

- Stephanos Constantinides is a professor of Political Science in Quebec, Canada and scientific contributor to the University of Crete.

Notes

- Demographic Report, 1971, Υπουργείο Οικονομικών, Λευκωσία, 1971, p. 26. see also S. Georghallides, A Political and Administrative History of Cyprus, 1918-1926, Nicosia, Cyprus Research Centre, p. 52-53, Theodoros Papadopoullos, Social and Historical Data on Population (1570-1881), Nicosia, 1965, John-Jones, L.W. Saint, The population of Cyprus : Demographic trends and socio-economic influence, London, Maurice Temple Smith, 1983.

- S. Geoghallides, A Political and Administrative History of Cyprus, Ibid., p.52, who refers to related bibliography

- ΑΚΕΛ(AKEL), Ο Δρόμος Προς τη Λευτεριά, Για Ένα Μίνιμουμ Πρόγραμμα του ΑΚΕΛ για τη Συγκρότηση του Ενιαίου Απελευθερωτικού Μετώπου Πάλης, Λευκωσία, 1952, Επανέκδοση, Αθήνα, Εκδοτική Ομάδα Εργασία, 1977, p. 50 (The Road to Freedom, For a Minimum Plan by AKEL for the Founding of the Unified Front for the Struggle to Liberation, Nicosia 1952, reprinted, Athens, Publishing Group Ergasia, 1977, p. 50)

- Hania(Inns, Χάνια), several of Turkish ownership and management; existed in all the cities of Cyprus until independence. In Paphos, for example, for many years until the 1950s, the largest accommodation was the “Brahimi Inn”(χάνι του Μπραΐμη) in the city center. Conductors and villagers who had to spend the night in the city ended up with their horses, mules or even donkeys, in these inns. Chanis existed also outside the cities on major roadways.

- Ihsan Ali, Τα απομνημονεύματά μου, Nicosia, 1980, p. 4.

- ΑΚΕΛ, Ο δρόμος προς τη Λευτεριά, , p. 50.

- Michalis Attalides, «Οι σχέσεις των Ελληνοκυπρίων με τους Τουρκοκυπρίους», at Γιώργος Τενεκίδης, Γιάννος Κρανιδιώτης, (επιμέλεια), Κύπρος, Ιστορία, Προβλήματα, και Αγώνες του Λαού της, Athens, βιβλιοπωλείο της Εστίας, second edition 2000, p. 424-425.

- Handbook of Cyprus, Λευκωσία, 1901.

- Ibrahim Aziz, Το παρελθόν και η πορεία της Τουρκοκυπριακής Κοινότητας, Nicosia, 1981, p. 20.

- Niyazi Kizilyϋrek, Ολική Κύπρος, Λευκωσία, 1990, p.15.

- p. 44.

- p. 20.

- p. 20. One could remark that since the beginning the Turkish Cypriot political leadership was completely dependent, first on British colonialism and then on Ankara. This situation continues to this day. In essence, Ankara used the Turks of Cyprus as a strategic minority to serve its own interests. And this in contrast to the Greek majority which was often in conflict with Athens or in any case the Greek Cypriot leadership dared, when it deemed it necessary, to oppose the suggestions of Athens.

- Michalis Attalides, , p. 420.

- Iacovos Tenedios, «Πολιτικές μετατοπίσεις στην τουρκοκυπριακή κοινότητα», in the collected works Ανατομία μιας μεταμόρφωσης, επιμέλεια Νίκος Περιστιάνης-Γιώργος Τσαγγαράς, Nicosia, Εκδόσεις Intercollege, 1995, p. 387. He also states that an attempt to establish a political organization among the Turkish Cypriots in 1913, which was given the name Cemaati-Islam Teskilati- Organization of the Islamic Community, failed.

- Niyazi Kizilyϋrek, Ολική Κύπρος, Ibid., p. 6. see επίσης Ιάκωβου Τενεδιού, Κοινωνικοπολιτική δομή των Τουρκοκυπρίων, δακτυλογραφημένη μελέτη, Υπουργείο Εξωτερικών της Κύπρου, Ιούνιος 1988, p. 35. Also of the same «Πολιτικές μετατοπίσεις στην τουρκοκυπριακή κοινότητα», Tenedios also refers to Turkish sources which show that the English were behind the founding of the Katak organization.

- Iacovos Tenedios, «Πολιτικές μετατοπίσεις στην τουρκοκυπριακή κοινότητα», , p. 389. The political developments since then within the Turkish Cypriot minority, under the leadership of Ankara, later led to the claim of the designation Community and after the invasion of 1974, the designation “Turkish Cypriot people”.

- Michalis Attalides, «Οι σχέσεις των Ελληνοκυπρίων με τους Τουρκοκυπρίους», , p. 420-421. Attalides emphasizes the role of Britain and later on of Ankara for these political processes in the Turkish Cypriot community.

- Nerfan Cahit, Kibris Turk Ogretmenler Sindikasi Mucadele Tarihi, τόμος Α΄, p. 4. Mentioned by Iacovos Tenedios, «Πολιτικές μετατοπίσεις στην τουρκοκυπριακή κοινότητα», , p. 390, who also gives the relevant source.

- Pavlos Tzieremias(Παύλος Ν. Τζιερμιάς), Ιστορία της Κυπριακής Δημοκρατίας, Πρώτος Τόμος, Αθήνα, Libro 2001, p. 156.

- Sener Levent, «Ο προδομένος ξεσηκωμός», Ο Πολίτης, June 1st , 2009.

- Sener Levent, «Ποιος ξεσηκωμός;», Ο Πολίτης 09/06/2009.

- Sener Levent, Ποιος μπορεί να αντέξει περισσότερο τη μη λύση; Ο Πολίτης , 11-06-2010

- In the synthesis and analysis of some dimensions of this chapter, because the events are recent, the Cypriot and Greek press were used as sources. Since with the technical means available to the reader today, especially with the storage of information available on the internet, certain things are easy to check, it was not deemed necessary to always make references. Furthermore, the author, according to the scientific perception that prevails in the social sciences, considers himself an Observer-Participant in the flow of events. In any case, some sources remain very useful. Such is the case, for example, with the book by Claire Palley, a British professor of international relations and constitutionalist, An International Relations Debacle, London, Oxford and USA, Portland, Oregon, 2005, who was – on behalf of the United Kingdom – a member of the United Nations Subcommittee on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities (1988-1998) and an advisor on constitutional issues to the President of Cyprus (1980-2004). Finally, a decade long selection of articles by the author, Κύπρος, Θραύσματα μιας εποχής, (2000-2010), στις εκδόσεις Αιγαίον (Λευκωσία), 2010 (Cyprus, Fragments of an Era, (2000-2010)), presents the latest course of the Cyprus problem.