Academics used to have privileges not enjoyed by the majority of the workforce: job security, flexible hours, access to great libraries, a slower rhythm that afforded them the opportunity to think, create and pass on their knowledge and passion to others.

“We wanted to become professors because of the joy of intellectual discovery, the beauty of literary texts and the radical potential of new ideas” Canadian professors Berg and Seeber wrote in their seminal book The Slow Professor, challenging the culture of speed and short-termism that has taken over university life.

Academia hasn’t been slow or sane for a while now. Which is perhaps why Manolis Melissaris abandoned his professorship at the London School of Economics a few years ago to move to Cyprus to pursue his passion to write fiction.

Academia hasn’t been slow or sane for a while now. Which is perhaps why Manolis Melissaris abandoned his professorship at the London School of Economics a few years ago to move to Cyprus to pursue his passion to write fiction.

His latest book, Peer Review (Amazon 2020, pp262), is a comic thriller set in an English red brick university. The narrator, Dr Michael West, is a charming outsider, a ‘slow school’ lecturer in Social Anthropology who finds himself at the centre of a fast paced murder mystery that amid faculty meetings, research paper submissions and break downs of heart-broken PhD students negotiates our notions of ethics and justice.

Melissaris has constructed an unlikely crime story that delivers, rather cleverly, a damning verdict on the state of today’s academic establishment exposing its administrative labyrinths, the dizzying futility of conference presentations, the obsession with metrics and targets, and the consequent barbaric competition between academics.

Dr West is part social scientist, part detective, part philosopher, part sharp forensic expert and most entertainingly full-time cynic. When a teasing colleague asks him whether he has taken his cynicism medicine he retorts that he had stopped because his condition is terminal.

“Universities are like monasteries” West claims, “some find shelter in them because they have already achieved serenity in their invariably misguided certainty about what is valuable in life, their intellectual ability, the meaning of the world… others, the relatively noble ones, join academia out of confusion about the world and their own lives…”

But West also claims that academia is harsher than the ‘real world’. “What is that ‘real world’ anyway?” he asks: “People obsessed with their self-interest? Being judged by people patently inferior to you in every way at every corner? Having to bend over backwards to please those who do not deserve to be pleased? Making gains at the expense of others? The ‘real world’ gang wouldn’t last a day in academia.” Possibly a veiled critique of the demoralising culture of corporatization that has taken over education.

After six years at the university Dr West believes his time is up for promotion. His teaching is solid, his peer-reviewed publications are, he tells us, at the very least acceptable, and he feels he has done well as Director of Post Graduate Studies. But the Promotion Committee informs him that his research, though sound, lacks vision.

“The point of research in the social sciences”, the ever cynical West asserts, “is rarely ever to solve problems; it is to invent them”. Which does explain why vision is required. Younger colleagues have jumped the promotion queue. He decides to take matters into his own hands. It is here that Melissaris’ expertise shines.

As a former Professor of the Philosophy of Law having spent hours challenging students to construct abstract philosophical arguments out of real criminal scenarios, he has concocted what on the face of it looks like an implausible crime story. Its paradoxes negotiate concepts of morality, punishment, plagiarism and police corruption all the while tracking the missteps of a disillusioned faculty and the hypocrisy of those operating in the ‘real world.’

Leaving a faculty party at the local pub late one evening West returns to campus and sneaks into his Head of Department’s office with the purpose of ‘adjusting’ the crucial recommendation letter to be sent to the University Promotions Committee. He fails to hear his HoD walk into the office, as it turns out, drunk and slurring. In a state of panic he reaches for a copy of Bronislaw Malinowski’s Crime and Custom in Savage Society which he pretends to have come to borrow. Within seconds his Head of Department is lying on the floor, dead.

We understand that when not murdered, being Head of Department is a kind of bureaucratic hard labour that sucks the life out of professors condemning them to endless meetings and cycles of reporting. The real story begins when it becomes clear that no-one in the department wants the now vacant post.

By this point I begin to think that Melissaris, who spent fifteen years teaching philosophy and criminal law in Manchester, Keele and the LSE might have been offered the opportunity to head some Department prompting him to chuck it all in and descend on Cyprus to pursue fiction writing. Who knows, perhaps it was Brexit.

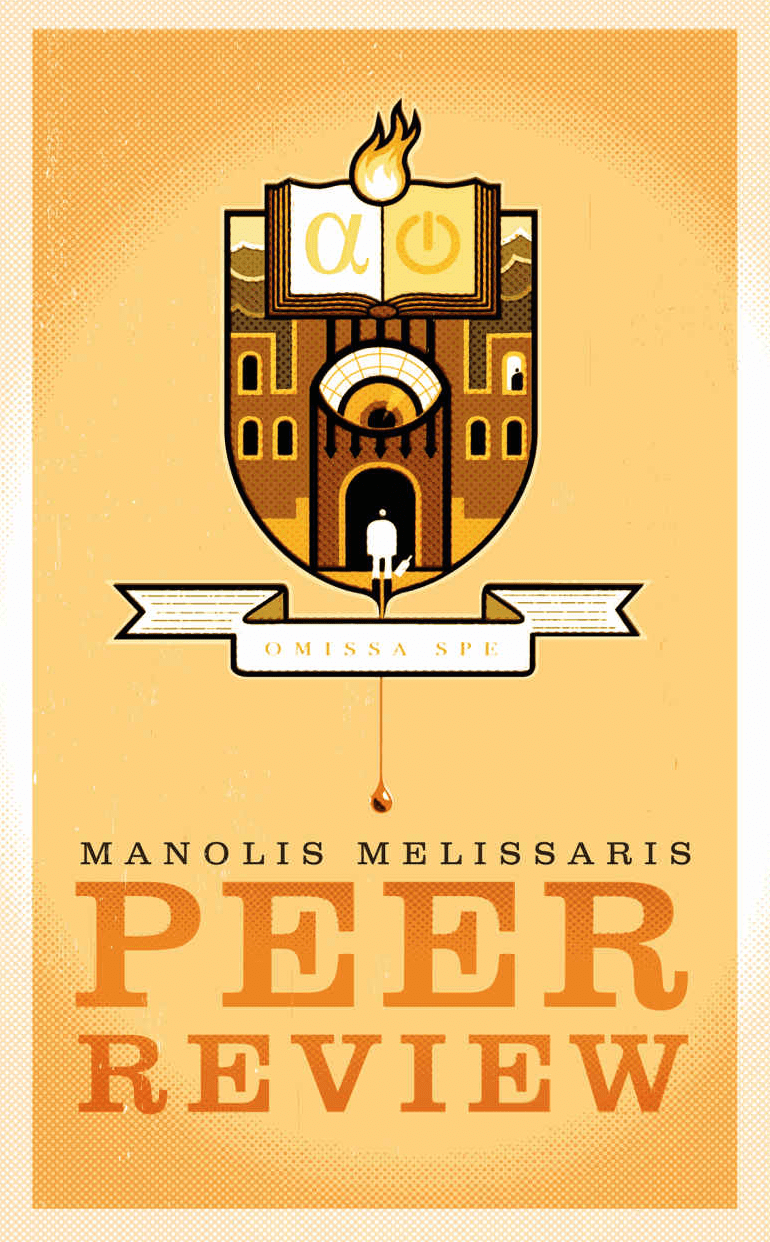

Whatever the trigger, on the evidence of Peer Review, it appears that the country has done wonders for his creative energy. I can’t help thinking, however, that on arrival Melissaris may have missed the Omissa Spe inscription flashing above the gateway into Cyprus’ real world.

* Abandon All Hope – The inscription at the entrance to Hell in Dante’s Divine Comedy. It is inscribed under the coat of arms adorning the cover of Peer Review.