It couldn’t happen here.

Ece Temelkuran lost her country to Tayip Erdogan’s religious-nationalist populism and has since gallantly been fighting to get it back.

One of Turkey’s most popular journalists she is now an international author and activist in exile.

One of Turkey’s most popular journalists she is now an international author and activist in exile.

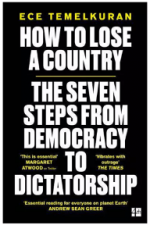

In How to Lose a Country: The Seven Steps from Democracy to Dictatorship she has produced an important and eloquently written book.

Some parts will prove awkward for readers whose countries had been on the receiving end of Turkey’s bullying and expansionism long before Erdogan’s theft made it worse for the Turks themselves. But trusting in Temelkuran’s obvious sense of history and in her intellectual integrity, she is likely to be aware of some of her readers’ potential discomfort.

The good thing is that her campaign to help build a new Turkey would not only reverse the deterioration since Erdogan’s election in 2003 but could also address the ills that preceded, perhaps even triggered, his arrival.

For a long time the West’s reading of Turkey had suffered from the absence of Turkish voices able to articulate the complexity of Erdogan’s playbook. It was not easy to understand how an imperfect democracy with no theocratic symptoms where the army had a disproportional role was dragged down the path of religious dictatorship. The West’s view was partly blinkered by the size of Turkey’s market and its geopolitical value. Yet some European capitals played along with Erdogan not out of any misreading or ignorance but out of willful capitalist self-interest.

The legendary journalist Mehmet Ali Birand, who used to work at Milliyet where Temelkuran was also an influential columnist, used to be the go-to source for deciphering Turkey’s politics. Useful though his analysis was, Birand often spoke as a representative of Turkey. Temelkuran brings something different. She writes as a representative of a universal, stateless liberal democratic movement, who just happens to be Turkish. Her Turkish experience is authentic, her concern is genuine, her arguments are rational and convincing.

It is a painful sign of the times that her analysis of the dismantling of Turkey’s institutions should serve as a manual on what should not happen elsewhere, and of all places in the United States and the United Kingdom.

During the early years of Erdogan’s AK Party Temelkuran toured the country and listened to the growing voice of a new formation labelled “the real people”. She became increasingly alarmed by how the marginalized, the desperate, those who claimed had been “disrespected” by the establishment, had begun to organise.

Under Erdogan the movement would soon pounce on the status quo, demand respect for their re-discovered religion. His cronies would go on to rig elections and spread fear among a retreating secular Turkish society.

Reasonable people in Istanbul would tell her “It couldn’t happen here” but it was already too late. The tactic was simple, says Temelkuran, “… spread confusion or start a fight between the established centre-right and centre-left politicians, poke away at the country’s fragile compromises and wallow in the disarray by stating that neither side was in touch with the demands of the real people…”

Erdogan distorted the narrative, reorganized financial and economic relations, steamrolled constitutional changes. He infiltrated institutions, including the judiciary and the army, imprisoned journalists, quashed any dissent and inevitably secured the devotion or submission of the masses. One morning the Turks woke up and exclaimed ‘This is not my country”.

Forced to flee Temelkuran explains how she later heard reasonable people in Washington repeat “It couldn’t happen here” just weeks before Trump’s election in 2016. She heard the same thing in London after the Brexit referendum.

The United States is not Turkey, and Trump is not Erdogan. But the hashtag #ThisIsNotMyCountry has been trending ominously in US social media feeds for some time. Trump may not be locking up journalists but he has eroded the US public’s faith in journalism. He may not be corrupting trials but he is insidiously shifting the balance in the US Supreme Court.

Information came to light this week in the New York Times on how Erdogan has actually compromised Trump by getting him to halt a criminal investigation into a state-owned Turkish bank suspected of violating US sanctions. Erdogan and his family have a stake in that bank. It is obvious that all this is not just about one country. The populist political mafia is colluding and spreading its dogma everywhere.

As the eastern Mediterranean’s tectonic plates and California’s winds remind Erdogan and Trump who, or what, is really in charge, it is important that the US and Turkey are snatched back from these demagogue thieves and that the competent democratically-minded are returned to manage the crises. Their dynamic must be interrupted. A Joe Biden victory on Tuesday could be a first step and one that would agitate Erdogan. A Biden defeat would mean that serial robberies will continue on an international scale.

Disturbing.