The Greek crisis: the debate continues

The Greek crisis which erupted in 2009 and is still underway will undoubtedly be the subject of many analyses and studies in the years to come.

- Prof. Louka T. Katseli

- GAC March 1, 2016

Economists, political scientists, public policy analysts and experts on European governance and policy making will continue to debate the nature and origins of the crisis, the effectiveness of the policies pursued by successive Greek governments and the role of the so called Troika, consisting of representatives of the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the IMF , in shaping the policy mix and imposing conditionality in the context of three successive MoUs, signed on May 10, 2010, February 18, 2012 and July 13, 2015.

At the core of the debate is the evaluation of the policy mix pursued, namely the effects of sharp fiscal consolidation and of substantial internal devaluation on growth, employment and the sustainability of public finances.

At the core of the debate is the evaluation of the policy mix pursued, namely the effects of sharp fiscal consolidation and of substantial internal devaluation on growth, employment and the sustainability of public finances.

Between 2008 and 2014 the cumulative loss of GDP exceeded 25% [1], the unemployment rate rose above 27%[2] and the general government gross debt to GDP ratio increased from 126.8% at the beginning of the crisis to 195% today (European Commission Country Profile 2015).

Between 2008 and 2014 the cumulative loss of GDP exceeded 25% [1], the unemployment rate rose above 27%[2] and the general government gross debt to GDP ratio increased from 126.8% at the beginning of the crisis to 195% today (European Commission Country Profile 2015).

Thus, there are many who argue that the “cure” imposed has in fact been “toxic”; others attribute these results to the lack of willingness or capacity of the Greek governments to implement the “pro-growth” structural reforms embedded in the programs; still others point their finger to more technical policy design failures , including the underestimation of multipliers, the lack of coherence across fiscal and monetary policies , the deleterious effects of a massive debt-overhang on investment incentives etc.

***

[1] GDP at market prices was reduced from 241,9 billion euro in 2008 to 177,6 billion euro in 2014 (Eurostat, database as of 25-02-16).

[2] Unemployment rate peaked in 2013 at 27.5%; in 2014 it was still 26.5% (Eurostat).

***

In view of the fact that such crises are likely to reoccur in the future in the context of the Eurozone, it is important to draw some pertinent lessons from the Greek crisis that could pertain to other Eurozone member countries with a special focus on the interplay between growth, sustainable public finances and social protection systems.

A short overview of the Greek Crisis

By 2009, Greece had allowed itself to become vulnerable to a speculative attack.

For a number of decades, the principal sources of growth were rising private and public consumption expenditures coupled with a rapid expansion of construction investment, largely financed by EU transfers, relatively cheap foreign borrowing and short term capital inflows.

For a number of decades, the principal sources of growth were rising private and public consumption expenditures coupled with a rapid expansion of construction investment, largely financed by EU transfers, relatively cheap foreign borrowing and short term capital inflows.

Since Greece’s entry into the Eurozone in 2001 and especially after 2004, foreign and domestic banks, underestimating the risks involved, extended credit to households, enterprises and state entities on the assumption that rising debt would continue to be rolled over under the same favorable conditions as those prevailing for Germany and other Eurozone members. While the large current account and budget deficits provided a clear signal of unsustainability, policy makers delayed timely action.

A speculative attack against Greek sovereign bonds and the euro erupted between December 2009 and January 2010 with spreads on Greek bonds rising to unprecedented levels.

A speculative attack against Greek sovereign bonds and the euro erupted between December 2009 and January 2010 with spreads on Greek bonds rising to unprecedented levels.

Speculators who had proceeded since 2007 to cover themselves against a possible default through purchases of CDSs, unloaded Greek sovereign bonds.

European institutions were caught unprepared. Unwilling and unable to intervene in secondary markets to stem the attack or to address the debt-overhang problem under fear of a “systemic crisis” and big losses for European banks with large exposures, they proceeded to create the EFSF and extend a bail-out loan to the Greek government in exchange for stringent austerity measures.

Actual disbursements from EU institutions and the IMF that were extended under the two stand-by agreements signed in 2010 and 2012 amounted to 215.7 bn euro.

A third agreement has been signed in July 2015 extending further loans of up to 86 billion for the period 2015-2018. So far, only 11% of bail-out loans went to finance the government accounts. The rest has been used to repay creditors, avoid the write-down of previous bad loans, pay back interest and capital operations .

A third agreement has been signed in July 2015 extending further loans of up to 86 billion for the period 2015-2018. So far, only 11% of bail-out loans went to finance the government accounts. The rest has been used to repay creditors, avoid the write-down of previous bad loans, pay back interest and capital operations .

The policy mix adopted under the conditionality terms embedded in the agreements, including severe cuts in wages, pensions and asset prices, resulted in an approximate loss of 25% of GDP, a dramatic rise of unemployment, increasing poverty and inequality.

As living standards deteriorated sharply, there was a rise of support for “outsiders” to the traditional bi-party system which brought into power , a small, left-wing party, SYRIZA, with a call for a credible “policy regime switch”.

As living standards deteriorated sharply, there was a rise of support for “outsiders” to the traditional bi-party system which brought into power , a small, left-wing party, SYRIZA, with a call for a credible “policy regime switch”.

Protracted negotiations between the newly-elected government and the European institutions ended in an impasse which resulted in the expiration of the 2nd stand-by program on June 30, 2015 and the imposition of a bank holiday and capital controls. Under the threat of an imminent Grexit, with weekly credit provided by the ECB solely through its Emergency Liquidity Assistance window, a 3rd Agreement was signed in July, extending a new loan of up to 86 billion euro to Greece under a three -year program.

The new program foresees, a more reasonable fiscal consolidation program, the recapitalization of the Banks within 2015, a new framework for the effective management of non-performing loans, product-market reforms and further pension reform, the restructuring of Greek debt and the creation of a Fund to manage public assets over a thirty year period.

Amid the challenges to comply with MoU prior actions and persisting funding and liquidity pressures, the four systemic Greek Banks proceeded to raise approximately 5 billion euros from private investors to cover the capital needs identified by the European Central Bank (ECB), following a Comprehensive Assessment (CA) of Banks’ portfolios and required provisions conducted in September 2015. By the end of 2015, following the injection of additional 5,4 billion euro of state-aid by the ESM for two of the banks, all four systemic banks have been adequately capitalized with their Core Tier 1 ratios exceeding 18%. They are expected to become eligible for normal financing from the ECB, once the first evaluation of the new program is completed. This would allow the lifting of capital controls hopefully within 2016 and the channeling of necessary liquidity to the real economy which will be a major boost to new investment and growth.

Despite the many challenges and risks ahead , a Greek restart appears plausible ; for this to happen however, all stakeholders need to work closely together and exhibit realism and flexibility in the implementation of the program by taking into account not only conditionality requirements but also the need for equitable burden-sharing and policy coherence. Drawing the necessary lessons from the past six turbulent years is a first step in this direction.

Lesson 1: Aggressive front-loaded restrictive policies can erode the sustainability of public finances

Between 2009 and 2015, the Greek economy achieved significant fiscal and current account rebalancing as a consequence of aggressive front-loaded fiscal consolidation and a sharp reduction of credit availability.

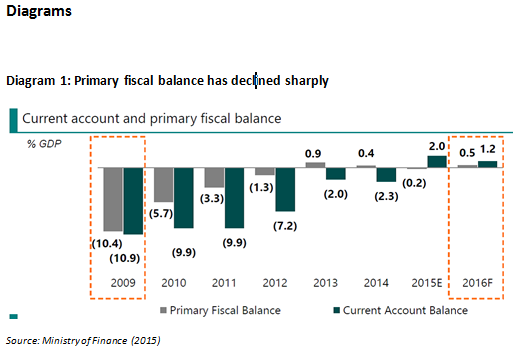

Within six years, the primary fiscal balance and the current account balance improved by approximately 10 pp and 13 pp of GDP respectively (Diagram 1); this has been the fastest and most intensive fiscal correction amongst all countries that underwent an economic adjustment program in Europe.

Within six years, the primary fiscal balance and the current account balance improved by approximately 10 pp and 13 pp of GDP respectively (Diagram 1); this has been the fastest and most intensive fiscal correction amongst all countries that underwent an economic adjustment program in Europe.

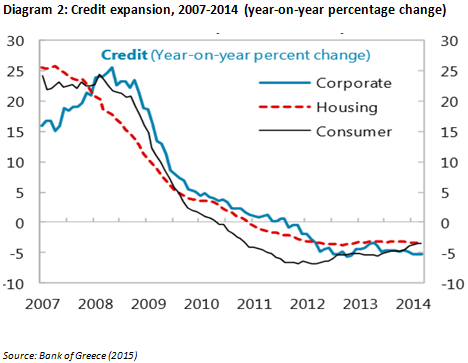

The severity of fiscal adjustment was coupled with a severe credit crunch ( Diagram 2 ) ; contractionary fiscal and monetary policies thus resulted in a cumulative loss of GDP amounting to 25 pp since 2007 and an unprecedented rise in unemployment rates.

The recessionary impact of these highly restrictive policies was exacerbated due to the predominance of micro and small -sized firms in the Greek economy. Unable to cover fixed costs or borrow from the banking system as demand fell, more than 200,000 firms have shut down[1] in the course of five years. A number of companies have relocated abroad[2] (Endeavor, 2015). The melt-down of Greece’s productive and entrepreneurial base is one of the fundamental factors that explain the prolonged recession and the inability of…

***

[1] IME GSEVEE, Survey, February 2014, Hellenic Confederation of Professionals, Craftsmen & Merchants (GSEVEE) Small Enterprises’ Institute.[2] In a recent study by Endeavour (2015), of 300 Greek businesses surveyed between 13 and 17 of July 2015, 23 percent planned to transfer their headquarters abroad and another 13 percent had already done so.

***

…the country to jumpstart growth relative to other countries’ experience with similar economic adjustment programs.

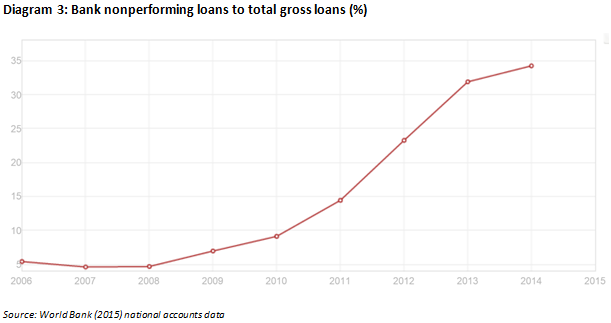

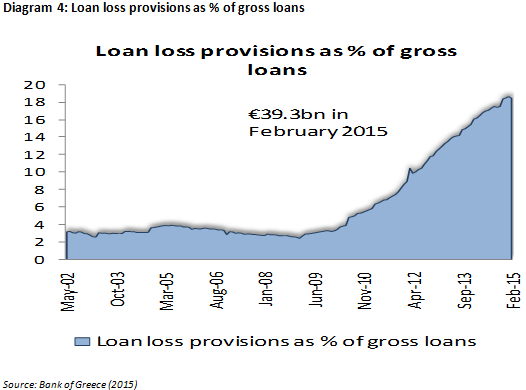

As disposable incomes of both households and firms declined sharply, tax receipts and social security contributions fell dramatically. Non-performing loans rose sharply across all portfolio categories – consumer and mortgage loans, SME and large corporate loans – forcing Banks to set aside increasing amounts of provisions to mitigate risks (Diagram 3). In December 2015, 46 billion euros were set aside as loan loss provisions by the banking system[1], exacerbating further the liquidity squeeze in the real economy (Diagram 4).

Last but not least, the recessionary impact of fiscal consolidation in conjunction with recourse to expensive short term or emergency financing sources, such as Treasury Bills and ELA, increased the Gross Public Debt to GDP ratio by approximately 50 ppts of GDP from 127 % in 2008 to 195% in 2015(Ministry of Finance, 2015).

Excessive austerity policies have thus been a toxic cure: due to their deep and prolonged negative growth effects, they have exacerbated rather than abated the sovereign debt problem while spreading the “over-indebtedness disease” to the domestic private sector; in so doing, they have put under serious threat the solvency of the banking system and the sustainability of public finances.

Lesson 2: The choice and sequencing of accompanying “structural reforms” is critical

Structural reforms, a critical component in all three MOU Agreements, were aimed to enhance competitiveness and to bring rapid economic recovery.

Empirical evidence, however, suggests that on average structural reforms do not appear to have strong short-run positive growth effects (Rodrik, 2015; Babecky and Campos, 2010).

Empirical evidence, however, suggests that on average structural reforms do not appear to have strong short-run positive growth effects (Rodrik, 2015; Babecky and Campos, 2010).

In fact, in the context of weak aggregate demand, these effects can even be negative, if structural measures end up reducing further disposable incomes and overall labor productivity (Caldera Sánchez, de Serres and Yashiro, 2015). The sequencing of reforms is equally important since positive growth effects from a given reform often hinge on the prior implementation of other reforms.

***

[1] Loan loss provisions amounted to 6 billion euro in December 2007.

***

The Greek labor-market reform agenda – a key component of the structural program of the past years- provides a telling example of the distortions that can ensue as a consequence of improper and untimely policy design and sequencing, largely due to an inadequate understanding of the macroeconomic environment in which these reforms are introduced and the structural features of the economy on which they are applied.

Labour market deregulation, mostly through the introduction of intermittent, temporary or part-time labor contracts and the reduction of employment protection started in 2010. By the end of 2011 and especially in 2012, while the economy was entering into a severe recession, they were complemented by the dismantling of collective agreements and favorable labour employment provisions as well as by the drastic reduction of the minimum wage. As a consequence, wages across the economy were reduced by approximately 30 per cent aggravating the recessionary effects of fiscal consolidation.

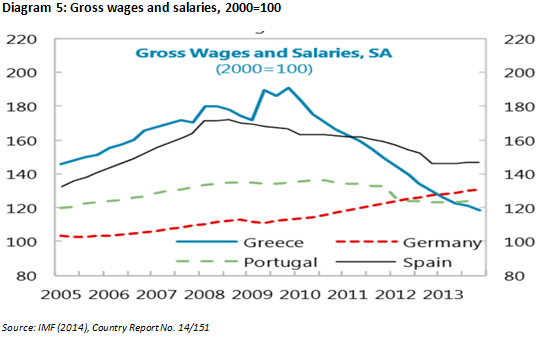

Βy 2014, gross wages and salaries in Greece fell below the corresponding wages in other European countries (Diagram 5). The substantial internal devaluation did not succeed in raising employment or investment demand, as growth prospects remained bleak, credit was severely restricted and uncertainty prevailed. Unemployment rates in fact peaked in 2013, while gross fixed capital formation plummeted from 25,7 per cent of GDP in 2007 to 11,6 percent in 2014 (Diagram 6). Last but not least, while price competitiveness as measured by relative unit labor costs (ULC) has improved by 16.5 per cent since 2005, energy and indirect tax cost increases resulted in a limited improvement of competitiveness as measured by final good prices[1] (Diagrams 7 and 8). Apart from energy and indirect tax cost increases, non-wage costs remained high due to increases in social security contributions and delays in product-market reforms to reduce oligopolistic practices, promote competition and lower the cost of doing business. While product-market reforms were mentioned on paper, neither the Greek governments nor the Troika placed them, at least till recently, on their “high-policy agenda” by identifying them as “prior actions” for a positive evaluation of the program. For example, even under the 2012 program, actions to improve the business environment and competition were limited to “legislative amendments to…

***

[1] The CPI-based real –exchange rate depreciated by only 5.6 per cent since 2009.

***

…remove disproportionate regulatory restrictions in four sectors (food processing, retail trade, building materials and tourism)” and for “opening the mediators’ profession to non-lawyers”; no priority was given to the urgent need for a drastic simplification of procedures and/or the reduction of costs for business licensing and operations across sectors, removing barriers to entry end enhancing competition in key sectors such as energy or transportation. As a result, a massive redistribution of income took place from wages to profits and from debtors to creditors.

Lesson 3: Upholding an effective social protection system is a prerequisite for sustainable public finances

The sharp reduction of net disposable incomes and the dramatic rise in firm closures have increased poverty and inequality to record levels. More than 44 per cent of Greeks found themselves at risk of poverty in 2013, up from 20 per cent in 2008 (ILO, 2014).

Around 400 000 families with children have no single working parent. Pensioners in particular suffered from sharp reductions in pensions, amounting in some cases to 50 per cent.

Around 400 000 families with children have no single working parent. Pensioners in particular suffered from sharp reductions in pensions, amounting in some cases to 50 per cent.

The inability to access the health system or afford medical treatment for a large number of the population increased vulnerability and lowered productivity. The Gini coefficient rose from 33 to 34 percent during the same period.

The severity of the austerity program coupled with the weakening of the social protection system has affected further the sustainability of public finances. Sharp cuts in personal after-tax disposable wage income and pensions of middle –income families have reduced their purchasing power and living standards as well as their capacity to pay taxes, social security contributions and debt obligations. By July 2015, delinquent obligations to social security funds only by SMEs rose to 36 percent of total obligations (Diagram 9), increasing the deficit in the social security system and delinquent obligations of the government to private providers of health services. In addition, as a growing number of productive-age, relative skilled adults and professionals have sought employment abroad, the ratio of working population to retirees has been reduced putting added pressures to public finances.

Looking ahead: In search of greater policy coherence

Given the lessons learned from past experience, effective implementation of the 3rd MoU Program requires greater policy coherence across fiscal policy measures, structural reforms and social policies.

This is essential to promote growth, safeguard the sustainability of public finances and support social cohesion.

The main challenge for the country so as to exit the present crisis and avoid future ones is to promote a sustainable economic transformation that would expand productivity and competitiveness through investment and technological change mainly in dynamic tradable sectors.

The main challenge for the country so as to exit the present crisis and avoid future ones is to promote a sustainable economic transformation that would expand productivity and competitiveness through investment and technological change mainly in dynamic tradable sectors.

Priority should thus be given to expand gross fixed capital formation by at least 10 percentage points of GDP till 2020 in sectors where Greece enjoys a comparative advantage in world markets, from the agro food sector, tourism, cultural and business services or shipping to logistics, ICT, pharmaceuticals, communications etc.

To do so, the structural reform agenda needs to give top priority on the one hand to investment –promoting measures (e.g. through simplification of licensing and business operations procedures, more stable, transparent and business friendly tax provisions, timely resolution of disputes in courts, strengthening competition policies etc.) as well as to extend funding at reasonable cost to viable firms and promising investments. Fiscal policy, most notably tax policy, should support these efforts rather than work against them. Last but not least, governance reforms should seek to promote public- private sector dialogue and partnerships, transparency and accountability (Katseli, 2014; Katseli, 2015). It is to the interest of all stakeholders to have Greece return to a sustainable growth path. The challenge is to agree on how to do it.

The arguments above and the lessons drawn from the Greek crisis should be interpreted not as a call for non-action but instead as a call for the adoption of timely and coherent reforms by governments to mitigate vulnerabilities before the eruption of financial crises. As stated in the introduction, Greece allowed itself to become vulnerable to a speculative attack in 2010 by postponing for two decades needed reforms that would have allowed it to enhance its price and structural competitiveness , expand greenfield investment and productive capacity and prevent the growth of deficits and over-indebtedness that triggered the crisis. The crisis could therefore have been avoided ; once it erupted , the adoption of an adjustment program was inevitable . In view of the inability of the ECB to act as a lender of last resort and the absence of institutional mechanisms to address such crises within the Eurozone , not adopting a program would have been highly problematic both for Greece and the Eurozone. The provision of funding allowed Greece to continue paying its debts and to avoid sovereign default ; it also prevented the eruption of a systemic crisis within the Eurozone with potentially devastating effects for major European banks and the euro.

With hindsight, both the first and the second programs could have been designed in ways that could have mitigated their severe deflationary and redistributive effects: fiscal adjustment could and should have been less severe, indirect tax and energy cost increases much smaller, and debt restructuring should have been addressed much earlier. Greater upfront emphasis should have been placed on product market reform and less emphasis-at least initially- on labour market and governance reforms, , that exacerbated the program’s deflationary bias[1]. In summary, priority should have been given to policy measures and pro-growth reforms with a view to lower the cost of doing business and enhance investment prospects. Such an alternative program was feasible and would have probably required less external financing ; it would have led to a more effective, sustainable and politically acceptable internal adjustment process which, at the end, could have prevented the impasse that led to the 3rd program and to a third recapitalization of the Greek banking system . It would have implied however a vastly different political arrangement between Greece and EU institutions, one built on greater consensus as to the origin and nature of the Greek crisis, the effectiveness of the reforms proposed in view of the characteristics of the Greek economy and more importantly the need for more equitable burden sharing across the various stakeholders. Under such an arrangement , European banks would have borne greater losses while European tax payers, …

***

[1] The Governance reforms through major administrative reforms adopted did not enhance the efficiency of government services but focused on the exit of 5,000 employees and the transfer of 25,000 civil servants to the mandatory mobility scheme instead

***

…not to speak of Greek wage earners and pensioners, would have borne a much smaller burden of adjustment.

Bibliography

Babecky J. and Campos N. (2011), “Does reform work? An econometric survey of the reform–growth puzzle”, Journal of Comparative Economics, 39, pp. 140-158.

Bank of Greece (2015), Annual Report of the Governor, Athens.

Caldera Sanches A., De Serres N. and Yashiro N. (2015), “Pursuing structural reforms in a difficult macro context: what should be the priority?”, NERO Meeting, OECD, June (http://www.oecd.org/eco/growth/NERO-22-June-2015-Structural-Reforms-in-a-Macro-Context.pdf).

Endeavor, Report on the Impact of Capital Controls, July 2015 (http://endeavor.org/research/endeavor-greece-releases-report-on-the-impact-of-capital-controls-on-local-businesses)

ILO (2014), “Greece: Productive Jobs for Greece”, Studies on Growth with Equity Series. (http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/—publ/documents/publication/wcms_319755.pdf)

IME GSEVEE (2014), Biannual portrayal of economic climate in small enterprises Survey, February (http://goo.gl/1IW8fC)

IMF (2014), IMF Country Report, 14/151: Greece

Katseli Louka (2015), “Why a win-win is possible for Greece and the EU”, World Economic Forum, Agenda Series

(https://agenda.weforum.org/2015/03/why-a-win-win-is-possible-for-greece-and-the-eu/)

Katseli Louka (2014), “Recent Fiscal and Labour Market Adjustments Experiences in Europe: Lessons for the Low-Income Countries”, CPD Anniversary Lecture, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Ministry of Finance (2015), State Budget 2016, Executive Summary, Athens

Rodrik Dani (2015), “Structural reforms and Greece: Lessons from other lands”, 2015 Kapuscinski Development Lecture and Athens Development and Governance Institute (ADGI-INERPOST), Athens.

(http://drodrik.scholar.harvard.edu/files/danirodrik/files/structural_reform_and_greece_-_lessons_from_other_lands.pdf?m=1443820618 and http://www.inerpost.gr/en/kapuscinski-development-lectures)

World Bank (2015), National Accounts Data 2015: Greece